The pestiferous child modulating the earth’s climate, together with his little sister. One of the most powerful climatic phenomena occurring on planet Earth. We are talking about El Niño (the child, in Spanish) and its counterpart La Niña. It’s making the headlines again because the Australian meteorological office has finally announced that an El Niño event has officially started in the Pacific Ocean [1], after its American counterpart had already done so a few months ago. Let’s see together why it is important.

The climate has its own cycles of change, not caused by any external forcing. The most important of these forcings is the accumulation of greenhouse gas in the climate due to human emissions; examples of natural forcing are volcanic eruptions and solar cycles. However, there is natural variability too, caused by processes such as El Niño. The influence of El Niño is so great that even recently, despite the evident global warming underway, there are periods of time in which the global-mean temperature rises little or not at all, while in others it accelerates noticeably. These periods correspond to La Niña and El Niño events respectively, as seen in this image.

El Niño and La Niña are essentially states of oscillation of the surface temperature values of the equatorial Pacific Ocean. When the former occurs, the ocean is warmer than usual and releases large amounts of energy into the atmosphere, accelerating global warming; when the second is present, however, the seawater temperature is lower, allowing energy to accumulate in the ocean and slowing down global warming [2]. The oscillation is monitored by measuring the average temperature of the Niño3.4 region, in the central Pacific. Being huge (it takes up almost an entire hemisphere!), it’s no surprise that the Pacific Ocean has such a large impact on Earth’s climate. The influence at a local level is even greater, especially on the people of South America, where the effects of El Niño are more intense in winter, hence the name “the child” in honour of the birth of little Isaac Newton, which incidentally coincides with Christmas. (Just kidding.)

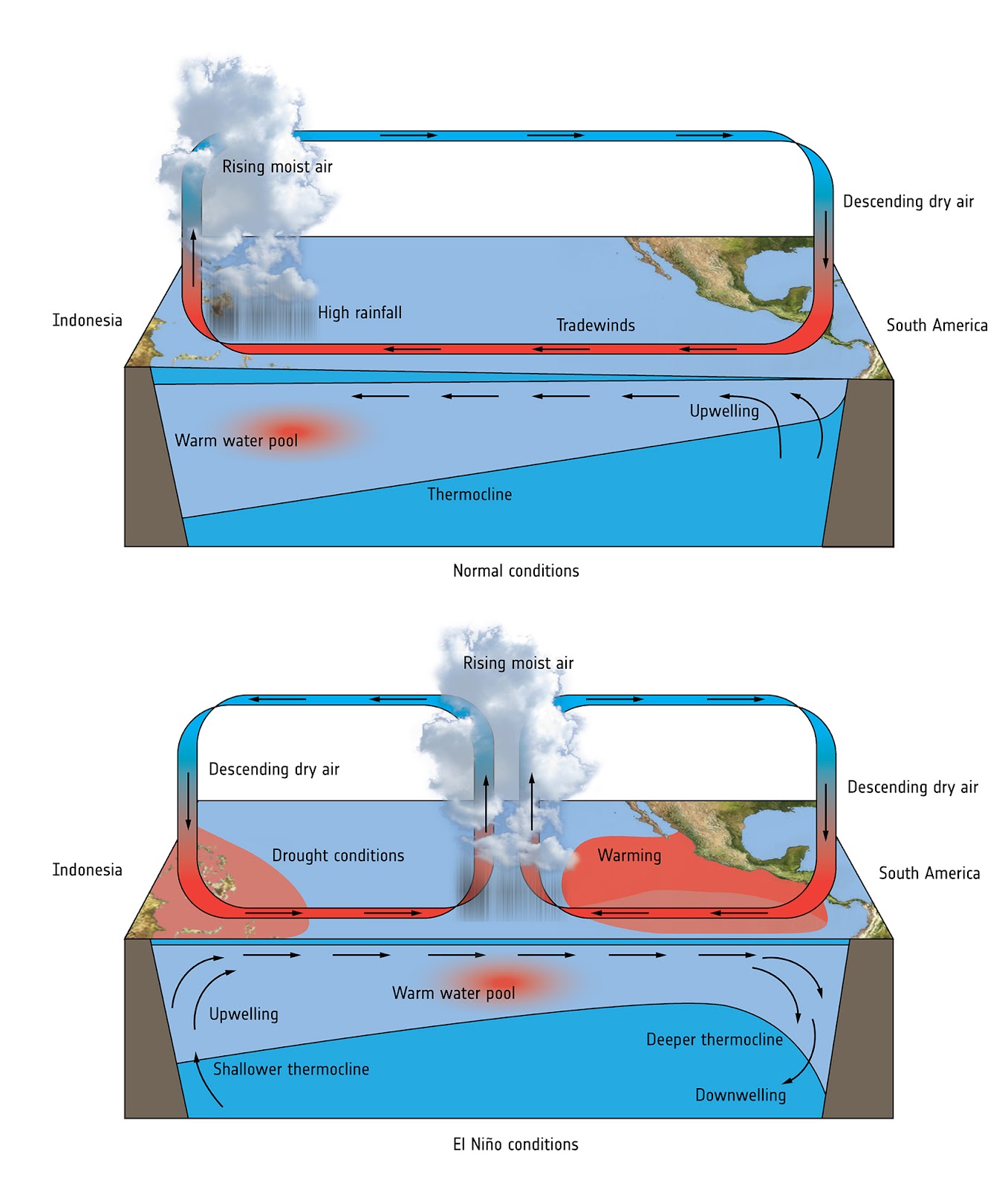

Both El Niño and La Niña belong to a cyclical process called ENSO (El Niño-Southern Oscillation), which combines El Niño and another phenomenon called Southern Oscillation [3]. It is a variation in the atmospheric pressure values at the sea level between Darwin (Australia) and Tahiti (French Polynesia). It is also an indicator of the strength of the atmospheric Walker Circulation, a cell in which air rises in the western Pacific near Indonesia, moves aloft along the equator to the opposite side of the ocean near South America, to then descend close to the surface and return towards Indonesia, thus originating the trade winds. The circulation was theorised by the English physicist Gilbert Walker in 1924 while he was studying the summer monsoons in India, hence the adjective “southern” because the phenomenon occurred south of the Indian subcontinent.

Due to the trade winds, at the surface of the western Pacific there is a pool of warm water fueling the rise, or convection, of the air over that region, thus closing the circulation of the cell [4]. In this condition, ENSO is in a neutral phase. The cold phase, i.e. La Niña, is essentially a strengthening of neutral conditions, with more intense trade winds pushing the warm water pool further westward and causing even greater convection over Indonesia, New Guinea, and Australia.

During the warm El Niño phase the Walker circulation weakens, the trade winds blow with less strength and the mass of warm water moves towards the centre of the equatorial Pacific, also causing the zone of rising air to move. Together with changing ocean currents in the equatorial Pacific, this causes the formation of a giant thermal anomaly in the eastern and central Pacific, with global repercussions. This has been happening from May 2023, as this NOAA animation shows. The last El Niño event was recorded in 2016, a record year for global temperatures, followed by three consecutive La Niña events that temporarily interrupted the increase in global temperature. The year 2023 is therefore a candidate to be the hottest year ever recorded so far. Summer 2023 was already the hottest ever, with record-breaking temperature especially in the oceans [5].

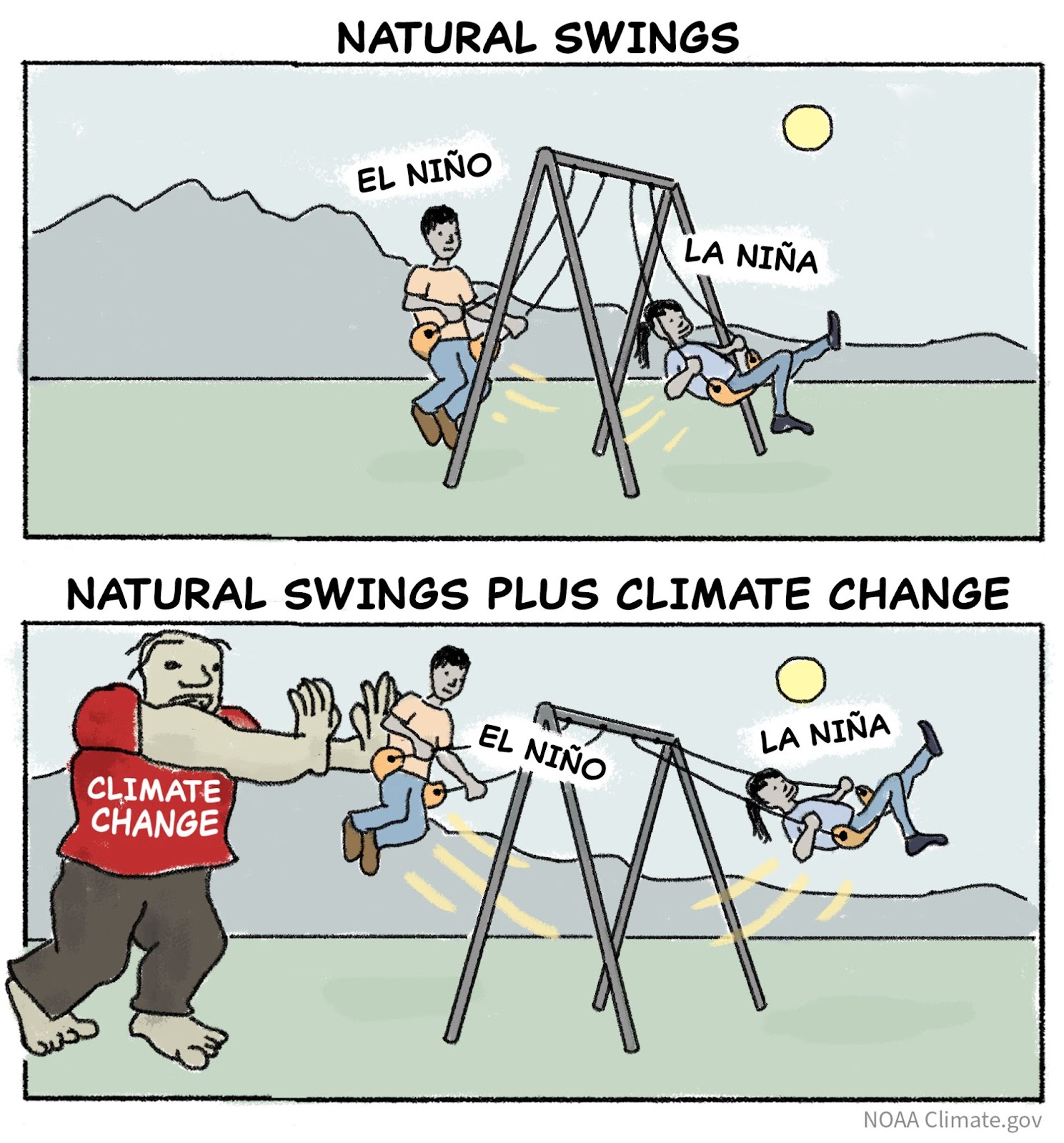

Due to its importance, the working mechanisms of ENSO are always being studied. The interaction between ocean and atmosphere is certainly paramount; it was first discovered in the 1960s, and led to the merging of the concepts of El Niño and Southern Oscillation to form the current name. Given ongoing climate change, it is crucial to know if and how ENSO is changing and how it will change in the future. We are already seeing an intensification of the hot and cold phases of the oscillation [6], exemplified by the cartoon below. The two children are swinging, alternating between warm and cold phases of ENSO; climate change, however, is pushing them, increasing the amplitude of the oscillation, thus leading to more intense phases. This will unfortunately have serious impacts both globally and locally, unfortunately much more serious than a fall from the swing.

Note: The original version of this article can be found here: https://www.noidiminerva.it/il-ritorno-del-nino/.

SOURCES

[1] http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/enso/outlook/

[2] https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/where-does-global-warming-go-during-la-nina

[3] https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/enso/soi

[4] https://www.esa.int/ESA_Multimedia/Images/2018/08/El_Nino

[5] https://climate.copernicus.eu/summer-2023-hottest-record

[6] https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/has-climate-change-already-affected-enso

Pingback: Did the Paris Agreement fail? – My Climate Science Blog