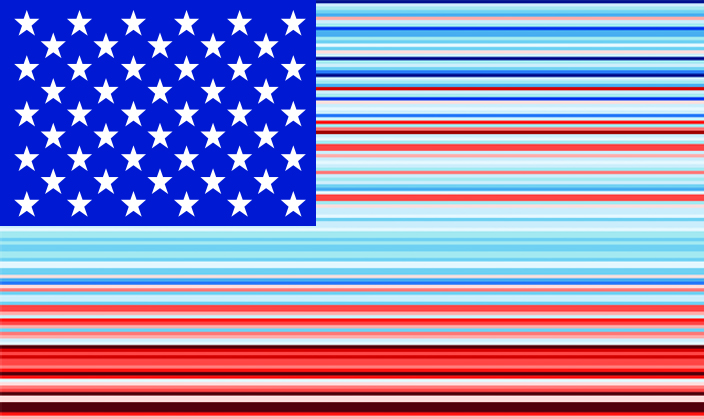

Ready, steady, go. As soon as it took office, the new administration of President Biden made the US rejoin the Paris climate agreement. This is a nice change of pace compared to the previous administration of President Trump, who decided to quit the agreement. For the occasion, the climate scientist Ed Hawkins produced a special version of his famous warming stripes. The Paris Agreement does not only concern the citizens of the French capital, but all of us. However, one question is legitimate: what is the Paris Agreement really?

One step at a time. To begin with, the agreement was approved in 2015, during a meeting held annually for 25 years now (except 2020). It’s called COP (Conference of the Parties) and is organized by UNFCCC, which is the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. This institution was founded in 1992 to address the most pressing challenges regarding climate change. In recent decades, its main aim has been to find a global agreement on limitation of greenhouse gas emissions, considered the main cause of the anthropogenic greenhouse effect (i.e., caused by human activities).

Let’s go back to the main topic. The Paris Agreement is the end product of COP 21, held in Paris in December 2015. They are probably the greatest success of “climate diplomacy” since the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which unfortunately was killed after a few years because the USA and Russia didn’t approve it. The Paris Agreement contains a series of unprecedented measures to fight climate change, or at least to mitigate its most harmful effects. In fact, the main aim of the agreement is to limit the increase in global surface temperature to less than 2°C compared to the pre-industrial period. This safety threshold represents a point beyond which the effects of climate change are thought to become very difficult to manage. I’ll talk about this again later.

Let’s take a break now. What does “climate diplomacy” mean? The answer lies in the functioning process of the COP. Being a conference of the parties, it is not only made up of scientists, but mainly of political and economic leaders from all over the world (called in jargon policy-makers), who must put into practice the decisions taken during the conference. This means that every COP is a kind of card game, in which the “polluting” countries (I think there is no need to give examples) try to play it down and save their face, while those most at risk (like the island states) try to bargain for more stringent measures. The final result is sometimes ambitious, as in the case of Paris 2015, other times it is disappointing, as in the case of Madrid 2019.

In the Paris Agreement, the parties put down their efforts to limit greenhouse gas emissions, to improve the mitigation of climate change, and to provide economic/technological aid to emerging countries to help them develop without polluting. These commitments are reviewed every 5 years. Afterwards, the countries that signed the agreement must incorporate the content into their national legislation. It is therefore not enough for the agreement to be signed. This is why President Trump was able to get the USA out of the agreement in his time.

However, there are also doubts about the effectiveness of this type of agreement. First of all, a country’s interest can change depending on the government in office (see the Obama-Trump-Biden case in the USA). Second, national targets are decided by individual countries. Diplomatic activity serves to ensure that, globally, national commitments ensure that the fateful threshold of 2°C is not exceeded. Third, there are no sanctions for those who do not respect their commitments. A watchdog body was founded and will be activated in 2024; national governments will provide reports on their progress, but it is unclear what countries at fault will face.

The issue of the 2°C threshold is fundamenta, so let’s try to understand where it comes from. Within the United Nations there is an agency dealing with the more technical aspects of climate change, called IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). It’s the world’s highest authority on climate change; it brings together the world’s leading climate experts and is divided into three sub-working groups, each dedicated to a different aspect of climate change (physical, socio-economic, mitigation). There’s more: every 7 years or so, the IPCC publishes an Assessment Report on the “state of the climate”, which contains all the knowledge we have on climate change and its effects. The latest report was published in 2014, while the next one should be released next year. In addition to these reports, others (called Special Reports) are published on more specific topics. Among those, one of the most important, published in 2018, is precisely about the temperature threshold that we must try not to exceed. The result? Unfortunately 2°C is too high, and our target should be 1.5°C. The problem is that much of this temperature increase has already occurred in the last few decades. Ed Hawkins keeps an interesting blog, in which he seeks to explain various aspects of climate change. He made this animation, calculating the increase in global temperature from 1850 to 2020. It really seems like it’s time to get moving (possibly in a sustainable way).

If you want to know more:

- See you in November for the COP 26 in Glasgow

- Summary of special report on the threshold of 1.5°C

- Data on greenhouse gas emissions

Note: The original version of this post can be found here: https://www.noidiminerva.it/welcome-back-usa/.