In another post, I have summarised the history of climate change in our planet’s remote and recent past. What can we say about the future?

To answer, we must first understand how difficult it was to understand the role of atmospheric constituents (like the famous greenhouse gas) in the radiative balance of the Earth’s atmosphere, i.e. the balance between incoming and outgoing energy. In fact, our atmosphere is a huge mixture of many substances. These behave differently when they interact with radiation, regardless of its origin (solar or terrestrial; yes, the Earth emits radiation). Some of the atmospheric components let the radiation pass through, while others reflect it, and yet others absorb it and re-emit it. To complicate matters, the behaviour depends on the wavelength of the radiation. A big mess.

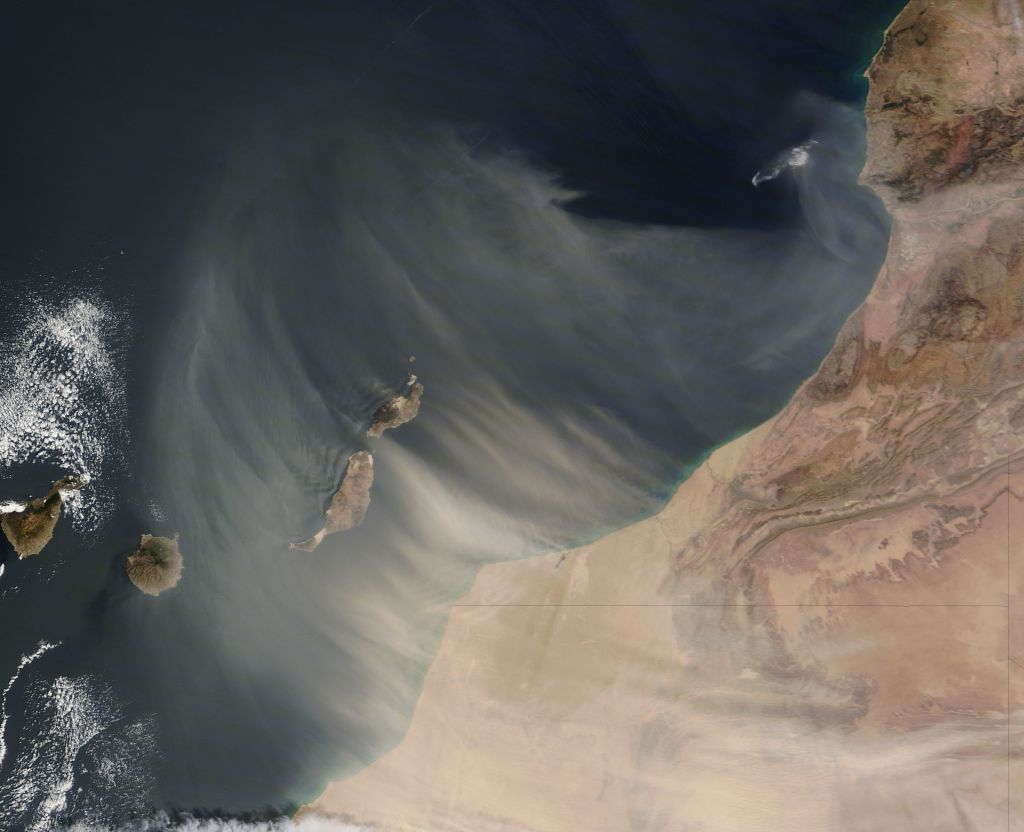

This is why initially the role of human emissions was misunderstood. Human activities are releasing many kinds of substances into the atmosphere, both in solid and gaseous form; as soon as their potential effect on the climate was realised, scientists immediately tried to understand the consequences. Using a rudimentary climate model, in the 1970s two scientists published an article in which they predicted a reduction in global temperature due to anthropogenic emissions (i.e., those produced by humans). Simply put, the study claimed that the reflective effect of anthropogenic aerosol (solid particles released by human activities in the atmosphere) on solar radiation was greater than the effect of absorption by greenhouse gases. This caused less solar radiation to reach the Earth’s surface, hence the cooling.

A few years later, Stephen Schneider, one of the authors of that article, realised that they underestimated the warming effect of greenhouse gases, while overestimating the cooling effect of aerosols. He remade the calculations using a more advanced numerical model, getting an increase in global temperature over time and no longer a decrease. He then published a book, called The Genesis Strategy, in which both interpretations and possible consequences on a climate, economic, and social level are described. The title is a reference to the Bible, more precisely to the book of Genesis, in which the pharaoh is advised to fill the granaries to face an imminent famine. Schneider wanted to underline how important it was, since we can predict climate change in advance, to take the necessary countermeasures before it was too late.

Since the atmosphere-radiation interaction is the main heating/cooling mechanism of the earth’s surface, its correct interpretation is fundamental to understanding climate change. Once this aspect was clarified (and it took some time, like several decades), one even more difficult remains: How do anthropogenic emissions change over time? The economy and technological progress changed the quantity and type of substances we humans produced over the centuries, from the industrial revolution (second half of the 18th century) to the present day. Similar changes will certainly happen in the future, but without a crystal ball it is impossible to know for sure how and when.

The need to predict the future climate, and above all our influence on it, led scientists to define different climate scenarios. What are those? First, different “future trends” of greenhouse gas emissions are estimated, then these are used to produce climate simulations; finally, the response is analysed using several indicators, such as the average global temperature, the average sea level, and the average extent of polar ice.

The world’s greatest authority in the study of climate, namely the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), is doing that. In its last report from 2014, and dedicated to the memory of Stephen Schneider who passed away in 2010, the IPCC defines 4 reference scenarios regarding greenhouse gas emissions:

- a pessimistic scenario, called business as usual, in which human emissions continue to increase as they have done so far;

- two intermediate scenarios, with emissions that initially grow but then reach stable values in the long term;

- an optimistic scenario, in which emissions are significantly reduced.

These scenarios are fed into complex economic/climate models, using an approach called Integrated Assessment Modeling (IAM). Based on the obtained radiation balance, the numerical model estimates climate change for decades or even centuries, as well as the related socio-economic effects. With these simulations we can also estimate the probability that a given amount of climate change may occur. This, together with the improvement of numerical models, makes the current simulations much more reliable than the one published by Schneider in 1971.

Among these scenarios, only the optimistic one manages to contain the global temperature increase to less than 2°C compared to the pre-industrial period, that is, before we began to emit large quantities of greenhouse gas into the atmosphere. This value was not chosen randomly, but represents a threshold within which climate change is thought to have non-dangerous effects. The maximum amount of greenhouse gases we can emit before reaching this fateful threshold is called carbon budget.

Even the history of this threshold, as with what it represents, has been rather troubled. It is used as an indicator to communicate the effect of human emissions in a synthetic way, even if it risks oversimplify a very complex phenomenon, with so many repercussions, and which by its nature is very difficult to summarise.

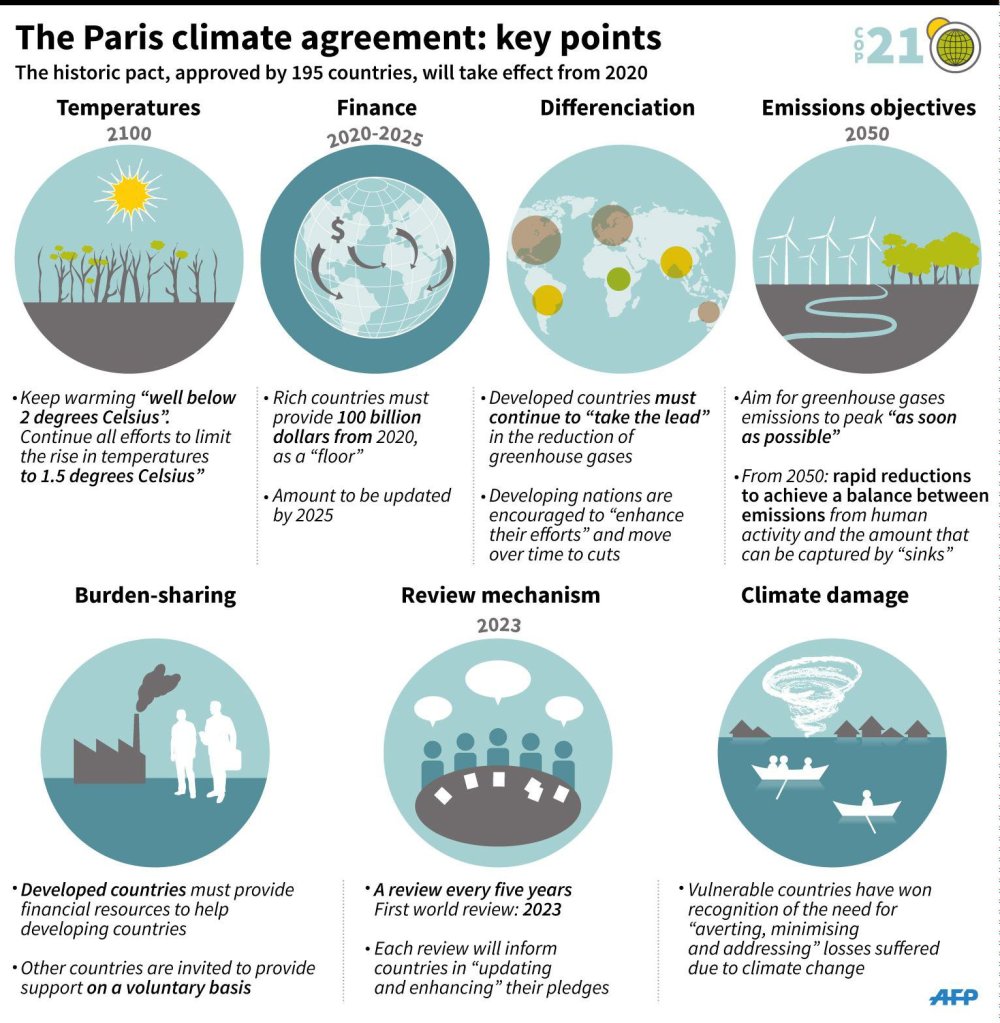

However, in December 2015 the twenty-first United Nations Climate Conference of the Parties (COP-21) approved the Paris Agreement based on a similar indicator, but with an even lower value (1.5°C), just to avoid risks. The agreement was signed and ratified by almost all countries in the world, despite the intention of the US President Donald Trump to make USA withdraw from the agreement. COP-21 also requested the IPCC to prepare a special report, expected to be published this year, to explain the importance of keeping global temperatures within the 1.5°C limit, besided the adaptation strategies we will need to adopt in the future to address climate change occurring right now. Because, like it or not, sooner or later we will have to deal with it.

If you want to know more:

– interactive map which shows various socio-economic indicators related to climate change;

– animated gifs which summarise the variations in the average global temperature, the average extent of Arctic ice and the average concentration of CO2;

– a biography of Stephen Schneider.