Imagine a dramatic change in climate, able to make our planet look like a huge snowball. Sounds like something out of a Hollywood film, doesn’t it? Who knows if anyone has ever thought of something like that… Oh right, unfortunately someone already did it (I’m looking at you, Emmerich).

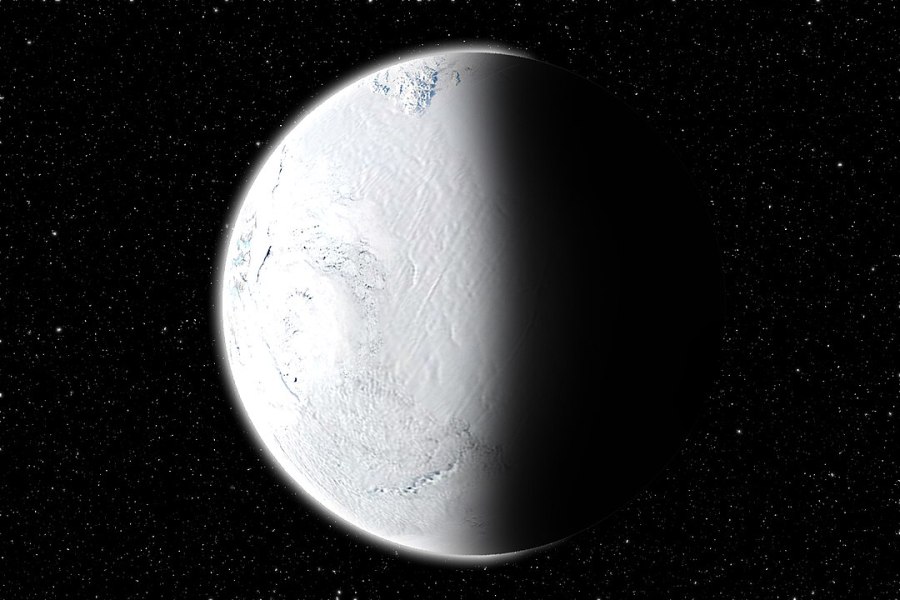

Anyway, the Snowball Earth theory exists and refers to a fascinating paleo-climate hypothesis (that is, concerning the Earth’s past climate). In short, the surface of our planet was almost completely covered by ice at least once in its “recent” history, around 650-700 million years ago. Not exactly last week. But why then do we care so much? Because it could happen again.

It may sound absurd, given that we are dealing with climate change and global warming. The point is that the Earth’s climate behaves in a non-linear way; in simple words, even a small change in some of its components (like the concentration of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, or the polar ice extent) can have shocking consequences. In the past, a reduction in the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gas might have triggered the following loop: due to a decrease in global temperature, the areas covered by ice expanded and contributed to further lowering the global temperature, reflecting more solar radiation back into space. These processes are called feedback mechanisms. Once the ice polar caps grow big enough, the positive loop causes them to grow even further, eventually covering the entire surface of the planet.

However, the first scientists who discovered this mechanism (called ice-albedo feedback) did not believe that it could lead to the planet being completely covered in ice, for a simple reason: they did not know if a way back existed. Once covered in ice, it was not clear how the Earth could free itself from the frozen grip. There are no thick layers of ice outside our window at the moment, so something made the ice melt. In fact, even if the surface was frozen, surely what’s underneath was not. It is believed that large volcanic eruptions might have contributed to increase the concentration of greenhouse gas, thus raising the global temperature. Within a few thousand years, the mid-latitudes and the tropics were ice-free. Climate feedback did the rest.

Clearly, considering we are talking about very old times, it is difficult to be sure that things actually went that way. In fact, there is evidence both in favour of the theory, for example the discovery of glacial sediments near the equator, and against it: some sediments were formed in too short a time, or not simultaneously with others found in other parts of the world. Furthermore, simulations carried out with climate models show that the Earth’s surface was never completely covered in ice. The most accepted hypothesis is that the Earth may have experienced in the past cold periods far more intense than the familiar ice age, but that the equatorial region remained free of ice. That allowed a steady development of life on the planet and helped (after millions of years) the ice to melt in other parts of the world.

Warning: This theory only applies to the last two billion years. Before then, a couple of intense glacial periods might have actually covered the entire earth’s surface with ice, but that’s much harder to pin down.